Tuesday, October 19, 2021 at 7pm

The Visual Taboo

155 Freeman Street, Brooklyn

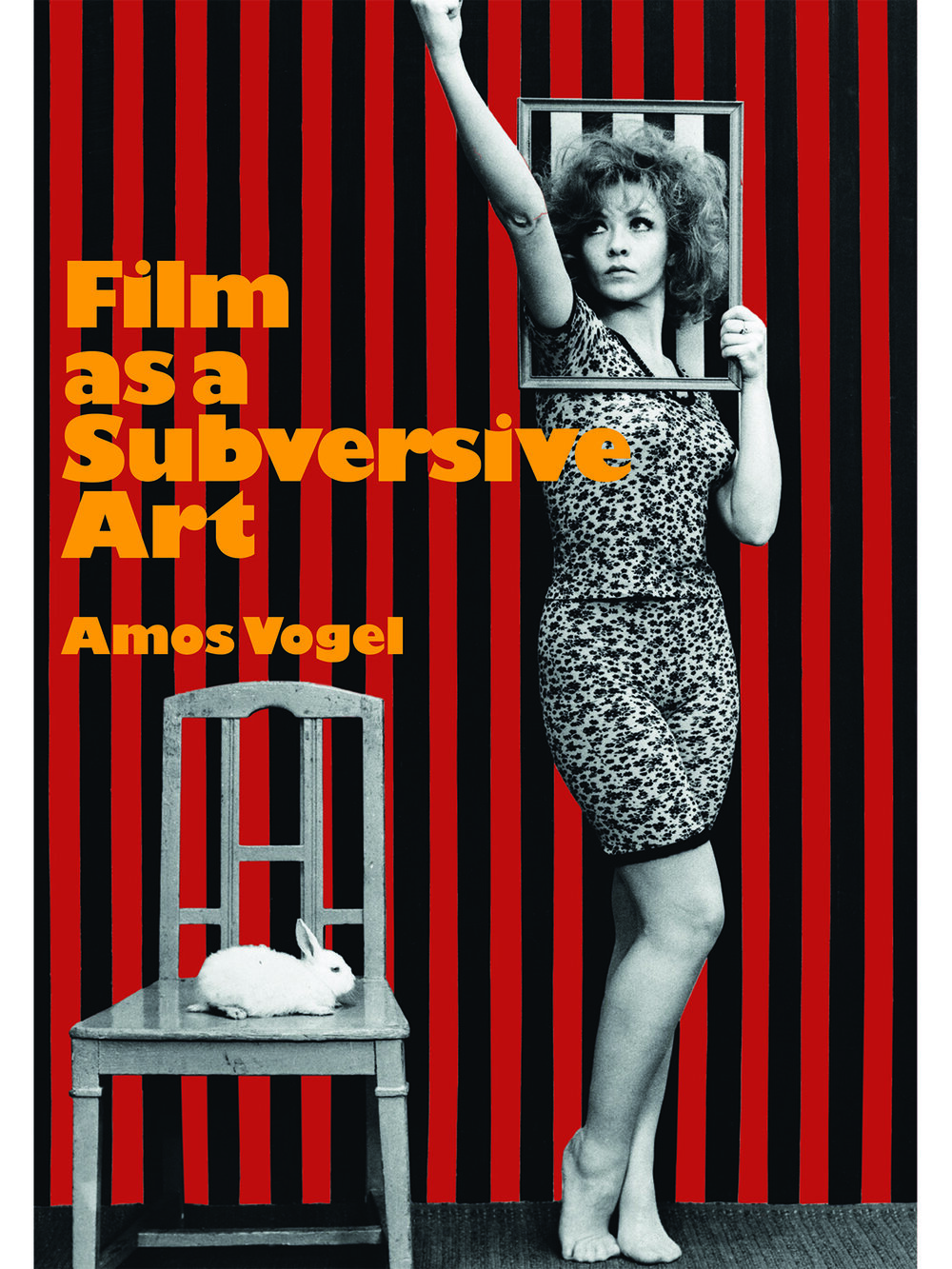

In 1974, Amos Vogel published his influential compendium of cinematic innovation, Film as a Subversive Art, which has recently been reprinted by The Film Desk. Copiously illustrated with images from hundreds of films, the book served not merely as an encyclopedia of important titles that Vogel had encountered in the course of decades of programming, but also an eloquent, even poetic expression of his ideas about the aesthetic and ethical values that the art of cinema offers human society. It remains one of the most sought-after historical texts on the history of avant-garde cinema for enthusiasts, even those who were born long after its first edition.

Vogel argued that the unique properties of cinematic exhibition allow film to function as a potential force for political awakening. “Subversion in cinema starts when the theatre darkens and the screen lights up,” he writes. “For the cinema is a place of magic where psychological and environmental factors combine to create an openness to wonder and suggestion, and unlocking of the unconscious.”

The book inspired generations of filmmakers and artists through its exhortation of the power of subversion and visual taboo as essentially revolutionary. In the often-cited chapter “The Power of Visual Taboo,” Vogel lays out a philosophy that many others sought to explore:

The attack on the visual taboo and its elimination by open, unhindered display is profoundly subversive, for it strikes at prevailing morality and religion and thereby at law and order itself. It calls into question the concept of eternal values and rudely uncovered their historicity. It proclaims the validity of sensuality and lust as legitimate human prerogatives. It reveals that what state authority proclaims as harmful may in fact be beneficial. It brings birth and death, our first and last mysteries, into the arena of human discourse and eases their acceptance. It fosters rational attitudes which fundamentally conflict with atavistic superstitions. It demystifies organs, and excretions. It does not tolerate man as a sinner, but accepts him and his acts in their entirety. To those who abolish taboos, “nothing human is alien,” as they marvel at the multiplicity of human endeavor and the diversity of an enterprise limited only by generic structure and cosmic environment.

While some of the subject matter that would have seemed taboo in 1974 may not appear as revolutionary today, the basic drives behind Film as a Subversive Art, and Vogel’s career as a whole, remain vitally important. Faced, as we are presently, with a rising tide of reactionary sentiment, Vogel’s insistence on using art as a means for raising the consciousnesses of everyday citizens has proven to be a mission worth sustaining.

This evening, Light Industry presents a selection of titles he highlighted as “Forbidden Subjects of the Cinema,” accompanied by his original descriptions from Film as a Subversive Art. Our program takes place in the context of a citywide celebration of Vogel’s centenary, alongside screenings at Anthology Film Archives, Film at Lincoln Center, Film Forum, Metrograph, the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of the Moving Image, and the Roxy Cinema.

Selective Service System, Warren Haack, 1970, 16mm, 13 mins

One of the most shocking documentary films ever made. A young anti-war American, to avoid the draft, calmly aims a rifle at his foot and shoots. For several endless minutes, he thrases about the floor in unbearable pain, in his own blood. The filming continues. “There was no attempt to alter the proceedings that took place.”

6/64: Mom and Dad [Material Action: Otto Muehl], Kurt Kren, 1964, 16mm, 4 mins

The Austrian avant-gardist Otto Muehl may well be the most scandalous filmmaker working in cinema today. Whether he is also the most subversive is the subject of a continuing international debate, with even some liberal critics denouncing him as fascist, or at least, anti-humanist. But it is a grave mistake to misinterpret Muehl's work as pornographic, thereby underestimating its seditious, anarchist intent...Muehl cannot be understood except as the product of a continent that experienced within half a century two world wars and the crushing trauma of Nazism; there is a stench of concentration camps, collective guilt, unbridled aggression, hallucinatory violence that—however relevatory—has the dimensions of an atavistic generalized myth of evil. If these are works of defilement—as they surely are—they reflect a society of defilement; they capture its essence by means of harrowing violence and perverse sexuality. To Muehl, the only way to exorcise this cruelty is by recreaing it in the protected environment of theatrical space, cruelly confronting the spectator not with fraudulent, fictionalized simulations but with the act itself.

Kirsa Nicholina, Gunvor Nelson, 1969, 16mm, 16 mins

That Gunvor Nelson is one of the most gifted of the new film humanists is revealed in this deceptively simple study of a child being born to a “counterculture” couple in their home. An almost classic manifesto of the new sensibility, it constitutes a proud affirmation of man amidst technology, genocide, and ecological destruction. Birth is presented not as an antiseptic, "medical" experience, but as the living-through of a primitive mystery, a spiritual celebration, a rite of passage. True to the new sensibility, it does not aggresively proselytize but conveys its ideology by force of example. With husband and friends quietly present, the pretty young woman, in bathrobe and red socks, is practically nude throughout; her whole body is seen at all times and, for once, the continuity between love-partner and birth-giver is maintained; she remains “erotic;” we never once forget that she is a woman and that the new life came from sexual desire.

The desperate romanticism of the new consciousness—a defiance of dehumanization—is manifest in the foolhardy willingness of these people to undergo the risk of a home delivery (though an apparently medically-trained person is present, and in their cool, “accepting” attitude of mankind as part of nature—the pantheism of the modern atheists. Thus she is not drugged, but fully conscious and, following the birth, experiences joy instead of exhaustion; there is so litle pain as to throw into doubt the necessity of centuries of female suffering. Instead of “specialists” coping with a “problem,” we witness human beings undergoing a basic human experience within the continuity provided by conjugal home and bed.

Quiet guitar music (composed by the father) accompanies the poetic, tactile images, unobtrusively recorded by the detached camera; no avant-garde pyrotechnics interfere with the intentional simplicity of the statement. As the baby, still half in the mother's body, begins to emerge, the mother smilingly takes its hand in her own and holds it. This tender gesture would not be possible in a hospital delivery because of drugs and antiseptic precautions. Perhaps, indeed, life should be lived as an open-ended adventure and “security” cast to the winds if we want to become human.

Sirius Remembered, Stan Brakhage, 1959, 16mm, 12 mins

The face of death; a daring, silent poem on a dead and gradually decaying dog, compusively recalled in interrelated, dream-like episodes, from many angles and in many seasons. The handheld camera, in its distraught movements, reflects the filmmaker’s anguish. A homage.

A Town Presented to the Jews as a Gift by the Führer, Vladimír Kressl, 1965, digital projection, 11 mins

An unprecedented historical document. The Nazi concentration camp of Terecin in Czechoslovakia was unique in occupying the area of an entire city, “presented as a gift to the Jews by the Führer” in an obscene gesture. In preparation for a visit by the International Red Cross “to investigate conditions,” the Nazis began producing what was to have been a 40-minute documentary film extolling the happy life of the camp's inmates and forced a Jewish prisoner, the well known actor Kurt Gerron, of Blue Angel fame, to direct it. About half of this unfinished film was accidentally recovered after the war by the Czechs and is incorporated in this instructive, horrifying object lesson of how “reality” can be manipulated and how false the “authentic” film image can be; for here, in this contrived documentary, we see the actual inmates of the camp-city at soccer games, listening to concerts, peacefully working at various jobs, tending their gardens in their spare time. It is difficult to decide what is more horrific, the “use” (by force) of human beings as actors in a portrayal of their lives that they knew to be false; or their constant, eager smiles to the camera (anything less may have meant instant death). “I like it here in Terecin,” one of the inmates says. “I lack nothing.” Within months, he and all the other hundreds of happy, smiling people in this film were exterminated.

Tickets - Pay what you can ($8 suggested donation), cash and cards accepted. Box office opens at 6:30pm.