Monday, September 12, 2016 at 7:30pm

Morgan Fisher's Phi Phenomenon + Newsreel's Community Control

155 Freeman Street, Brooklyn

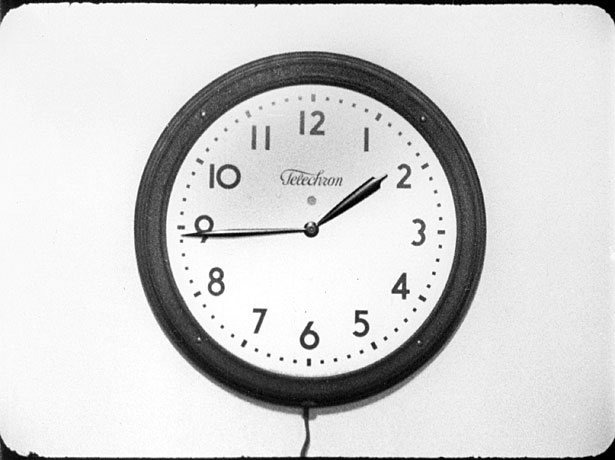

Phi Phenomenon, Morgan Fisher, 1968, 16mm, 11 mins

Community Control, Newsreel, 1969, digital projection of 16mm, 50 mins

On January 25, 1968, Jonas Mekas declared in his Movie Journal column for the Village Voice that “December 22 will go down in the history books of cinema. Some thirty film-makers—cameramen, editors, soundmen, directors—gathered at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque and created a radical Newsreel service.” Trumpeting the urgent necessity of such an enterprise, he then proceeded to republish an announcement from this recently formed outfit, simply dubbed Newsreel.

“The Newsreel,” the statement explained, “is a radical news service whose purpose is to provide an alternative to the limited and biased coverage of television news. The news that we feel is significant—any event that suggests the changes and redefinitions taking place in America today, or that underlines the necessity for such changes—has been consistently undermined and suppressed by the media: Therefore we have formed an organization to serve the needs of people who want to get hold of news that is relevant to their own activity and thought...The Newsreel films will reflect the viewpoints of its members, but will be aimed at those we consider our primary audience: all people working for change, students, organizations in ghettos and other depressed areas, and anyone who is not and cannot be satisfied by the news film available through establishment channels.” The collective would go on to produce a vital chronicle of a turbulent era, documenting student revolts at Columbia, the violence that erupted around the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, feminist protests against the Miss America pageant, and the case against the construction of Lincoln Center, which displaced thousands of Latino families. For tonight’s screening, Light Industry presents one of their most fascinating and fiercely dialectical efforts, Community Control.

The film unfolds during a crisis. In 1968, an experiment in decentralization at school districts in Ocean Hill-Brownsville and East Harlem, sponsored by the Ford Foundation in cooperation with the New York City Department of Education, gave way to calls for community control of those districts by local Black and Latino families. Area residents, organizing against what they saw as educational colonialism, demanded total oversight of every aspect of their children’s pedagogical environment, from curriculum to staffing. But when the new community boards requested the reassignment of certain racist faculty members, they came into direct conflict with the teachers’ union. This struggle for self-determination found Black Power squaring off against organized labor, culminating in a city-wide teachers’ strike, with police brutality and charges of anti-semitism further troubling the waters.

Through interviews with community organizers, visits with classrooms where teachers cover American history from a Black Nationalist perspective, and direct participation in acts of protest, Community Control jettisons any notion of documentary objectivity associated with the cinema vérité films of the same era. Newsreel’s editors punctuate these raw moments with explosive collages of audio and still images, a strategy of montage in line with the contemporaneous formal maneuvers of similarly engagé films like Santiago Álvarez’s Now or Carolee Schneemann’s Viet Flakes.

Morgan Fisher’s Phi Phenomenon, made the same year Community Control was recorded, likewise takes the educational scene as its point of departure, but using a very different scale of reference. In the minimalist strain of early structural film, Fisher’s work depicts, in a single, unbroken shot, the real-time movements of an iconic, institutional classroom clock. “Even if we don’t see any motion from one instant to the next,” Fisher writes, “we know that motion is occurring: as the film progresses, we see that the minute hand is no longer where we saw it before...Because we don’t perceive the motion directly, we rely instead on memory to lead us to the conclusion that motion has occurred.” Phi Phenomenon’s essentially imperceptible action makes for a film that gives the viewer none of the pleasures that commercial cinema provides: “There are no surprises. There is no variety, no increase in tension, no comic relief to relax it, no rising action, no climax, no denouement.”

In the broadest sense, both Community Control and Fisher’s film deal, in extremely different ways, with how cameras might scrutinize the perception of progress—whether political or temporal. But both also suggest how investigating the events of everyday life with renewed attention can lead to a reconsideration of the viewers’ place in the world, and the structures that inform that situation. Indeed, Fisher’s remarks about Phi Phenomenon prove surprisingly resonant with Newsreel’s project. “Why make a film of something that is redundant with something the viewer can see for himself or herself in daily life?” Fisher asks. “The answer is as obvious as the question. No one in daily life looks at a clock for eleven minutes. There is never a need to. And even if you set yourself to this task, you will find it very difficult, most likely impossible. But a film of a clock makes demands on you. You have to decide what your relationship to it is. You can always get up and leave, but if you stay, the film makes its demands on you, and you have to negotiate your relationship to it.”

Tickets - $8, available at door.

Please note: seating is limited. First-come, first-served. Box office opens at 7pm.